- © 2003 - 2025 Dynamix Productions, Inc. Contact Us 0

If we look back over the last 140 years of sound recording, it seems that formats come and formats...come back. I've written many times in these newsletters about nearly dead technologies that seemingly get resurrected out of nowhere, such as the vinyl record, the cassette, and AM radio. The younger generations are partly responsible for breathing new life into these old formats, but most stand on their own merits.

Vinyl records have an aesthetic appeal. It can be held in your hand. If you look closely at the grooves, you can literally see the sound. Loud, busy sections are very compact, while slow, legato passages are spaced far apart. It's like stepping in close to a Rembrandt painting to see the brush marks. When you play a record, you take an active part in listening. You must clean the surface, place the needle in the groove, and turn the record over to hear the other side. The sound of a record played on a good audio system has a distinct purity to it. Apart from the scratches (which sometimes add character and flavor), the sound can be less harsh than a digital version. The continuous sound of the stylus' friction in the bottom of the groove brings warmth. Plus, records are like animals presumed to be extinct, roaming the earth until someone rediscovers their existence. There are thousands and thousands of recordings that never made the transition to a digital format. They're hiding in some basement, yard sale, or record bin just waiting to be found.

The new fascination with cassettes is a bit curious to me. This was a format born for convenience, not quality. As reel-to-reel recorders shrunk in the 1950s and 60s, the play time of an audio reel did too. For the home user, 5- and 7-inch reels became popular over the larger 10-inch reels. The diminutive 5-inch reel usually held 30-45 minutes per side (or 60-90 minutes if an ultra-slow speed was available), but most of these consumer-oriented units only recorded mono sound. They were great for documenting family events or to send "audio letters" across the country (see my article "Audio Letters to Home" about families and GIs during the Vietnam War). But having to thread a fidgety tape onto a plastic reel just to listen to music was cumbersome.

The small compact cassette was the ideal replacement for open reels when it came along in the mid-1960s. It could be quickly loaded in a player and started. It held up to 90-minutes of stereo music (later 120-minutes with thinner tape), but the sound quality was inferior to reel-to-reel. No matter, consumers loved the portability and economics of cassettes. By the time cassette technology matured and the quality of recordings got better, they couldn't compete with the new kid on the block: the audio CD. This newfound interest in cassettes, especially by bands that release their music on them, has me flummoxed. There is only one manufacturer of cassette tape in the world, which leads enthusiasts on the hunt for NOS (new old stock), there are no high-quality recorders being made anymore, and nobody really loved the sound of cassettes when they were ubiquitous. We just accepted them as a convenient shuttle format to get from point A to point B. The only reasons I can come up with for their renewed popularity are: It can be held in the hand; It's a unique calling card; The "mixtape" is a hands-on love letter to music; And the discovery of NOS is intoxicating. If those are the only reasons, then I get it. But if it's for the sound...

More recent formats that may or may not be poised for a comeback someday are the audio CD and the mp3. Invented in the 1960s and brought to market in the 80s, the CD is currently on life support. I'm not sure it will have as large of a comeback as the LP, but it is a physical format that can be held in the hand. The mp3 file is a stubborn format that won't go away despite many superior alternatives. They are to a CD what cassettes were to reel-to-reels: convenient, compact, but woefully inferior. Maybe twenty-years from now it will be "cool" to "email" an mp3 to friends that have a "desktop" computer with Windows 95 and "speakers" to hear it on.

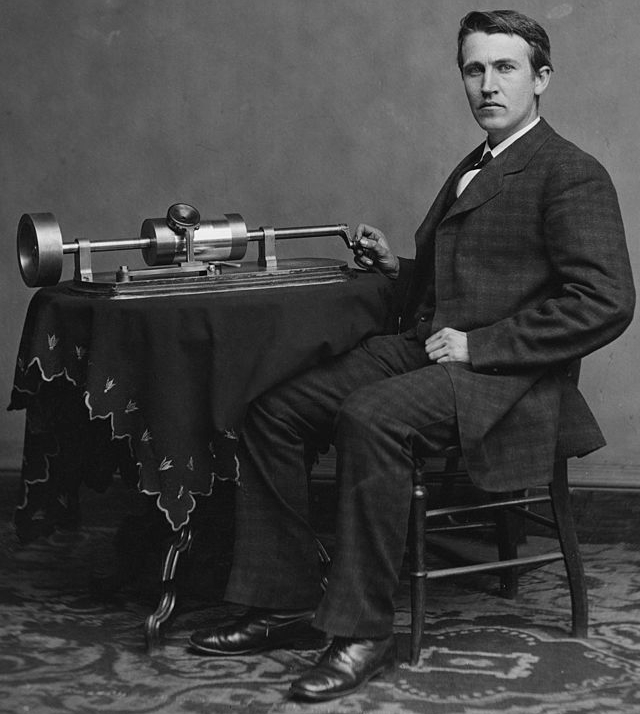

As if we are downgrading our expectations even more, the latest format that is getting some new attention is the wax cylinder. Are you cringing at the thought of having to go find an Edison Gem phonograph player to hear the latest Billie Eilish single? Don't worry, most of the effort at raising the dead is for preservation, although there is one band that has released new music on wax cylinder. Nameless Dreamers is a collaboration between Equip and R23X. Their music is reminiscent of a video game, maybe because they're both game music composers. Even their website is an homage to retro games. In 2021, they released two songs on 4-minute wax cylinders. YouTube vintage audio guru Matt Taylor (Techmoan) recently demonstrated an Edison Gem phonograph player by playing one of the songs.

But Nameless Dreamers' tunes aren't the first to be released since the early 20th century. In 2013, Justin Martell and Benjamin Canady released 50 cylinders of Tiny Tim‘s 1979 performance of “Nobody Else Can Love Me (Like My Old Tomato Can).” The release fit right in with Tiny Tim's style of performing tunes from the early days of the phonograph. Others have been trying it as well, like this heavy metal band recording in 2018 (shouldn't that be heavy wax?). If you want to release a new tune on wax, or buy century-old tunes re-recorded onto new wax cylinders, there are still a few companies providing this service. The Vulcan Cylinder Record Company in Sheffield, England is one, and has a catalog of old recordings that you can impress your friends with on your renovated player.

Early phonograph recordings are the target for digital restoration by the New York Public Library. It had digitized only 6% of its 2,700 cylinder collection before it recently received the Endpoint Audio Labs cylinder playback machine. Designed by Nicholas Bergh, the machine reads and digitizes the grooves on the outside of the cylinder with a laser, rather than a traditional needle and modulator. Its software smooths out the imperfections of the cylinder rotation that cause "wow," and cleans up surface noise and scratches. The usual erosion of the groove is avoided since no mechanical device actually touches the surface. You can hear a restored recording on this SoundCloud link. Another option for historians is a modern phonograph player from Mechanical Concepts. With an electric motor (instead of a hand-cranked spring motor on the original), it allows the use of a modern cartridge and stylus.

Why preserve these old recordings? Why not! These first recordings are a part of human history. We will be able to hear the voices of important people, long-forgotten musical styles, and incredible performances. We can study the material to better understand how this new media influenced society, and how it helped shape future recordings. And you never know, we might discover a new recording star, a hundred years in the making!