- © 2003 - 2025 Dynamix Productions, Inc. Contact Us 0

"I bought a Dutch barge and turned it into a recording studio. My plan was to go to Paris and record rolling down the Seine."

Pete Townshend, The Who

I'm conflicted on the topic of recording music at home. The business part of me frets about studios losing out on billable hours. The musician part of me relishes creating art in a non-pressure environment. But the history of artists recording radio-ready songs in their humble abodes goes back further than you might imagine. Let's explore how affordable home music recording for the masses came to be, but also look back at the origins of this revolution in recording.

"Hostilities will cease along the whole front from 11 November at 11 o'clock."

Marshal Foch, the French commander of the Allied forces via radio atop the Eiffel Tower.

This week marks 100 years since the end of the war to end all wars, known today as World War One. In 1918, on the 11th hour, on the 11th day of the 11th month, 1,500 days of fighting came to an end. The armistice was agreed upon just six hours earlier in a railway car halfway between Paris and the Western Front. What's remarkable is the speed at which most troops were informed of the impending armistice. This war, like in so many other ways, forever changed the world of communication.

"Hello from the children of Planet Earth"

From the gold records aboard the twin Voyager spacecraft

Vinyl is the format that won't die. It'll probably still be around after humans are extinct and our sun has gone supernova. Perhaps in eons, Voyager spacecraft with the golden records aboard will meet distant stars and future vinyl lovers. But in this eon, people will not stop pushing vinyl to its limits. Mad scientists and crazy artists like putting something other than music on it - or in it. More on that later.

Read More...

"Treat the recording studio as a laboratory for conceptual thinking — rather than as a mere tool."

Brian Eno

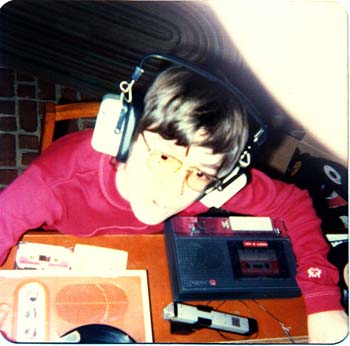

When I was young in the...cough...60s and 70s, the only real glimpses I got inside a recording studio was through television and movies. There was a smattering of documentaries and behind-the-scenes footage of studios and radio stations. I was always straining to see the control board and tape machines, or marveling at the cavernous studio on the other side of the glass. It was absolutely riveting to peek inside them and see how a record was made. The 8-foot long mixing console was often shot through a fisheye lens. Long-haired musicians were sunk down into a couch smoking cigarettes (?) and listening to their masterpiece. And there were close-up shots of that big fat 2-inch tape rolling past the heads of the recorder.

"He who knows that enough is enough will always have enough."

Lao Tzu

Father of Taoism

When is enough, enough? When do you stop finessing, polishing, correcting, perfecting, or otherwise fixing something important you're working on? When you're done – either because of deadline, budget, or exhaustion – are you satisfied? Something I like to say about my favorite projects is that I'm never really done with them, I just ran out of time

"My roommate got a pet elephant. Then it got lost. It's in the apartment somewhere."

Steven Wright

It started with insects. Caitlin O'Connell-Rodwell, PhD, an ecologist at Standford University, was working on her master's degree in entomology. Part of her research included recording love songs of Hawaiian planthoppers. They were communicating seismically (with really, really low sounds) through their limbs. Later, O'Connell-Rodwell was observing elephants in Namibia when she noticed the herd freezing, flattening their ears, and raising up on their toes. After field tests, she concluded that elephants can listen through their limbs and recognize warnings from particular elephants or herds miles away. Sensing low vibrations in the ground, elephants have been known to travel hundreds of miles toward storms for water, and flee threatening helicopters a hundred miles away.

“My dear girl, there are some things that just aren't done, such as drinking Dom Perignon '53 above the temperature of 38 degrees Fahrenheit. That's just as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs!”

James Bond

"Goldfinger" (United Artists)

The other day, someone said to me, "You must have golden ears." He was referring to my profession as an audio engineer. He assumed that I physically had much better hearing than the average person. I don't. In fact, I often have trouble hearing conversations at loud parties and can't hear high-pitched whines that drive 20-somethings crazy. But I do think I have better hearing than a lot of other middle-aged folks only because I've protected it all these years.

“The only real way to disarm your enemy is to listen to them.”

Amaryllis Fox

Writer, peace activist, former CIA Clandestine Service officer

Eavesdropping on the enemy in times of war can be essential to victory. During World War Two, a tucked away family farm in New England would save thousands of lives while being a key to Allied victories over Germany and Japan.

"The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere."

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

What did Paul Revere's famous midnight ride from Boston to Lexington sound like in April 1775? If you were there, you might recognize the approaching horse as a Narragansett Pacer mare. This once popular breed of horse, now extinct, was known for its ambling gait: a smooth riding four-beat gait that is faster than a walk, but slower than a canter or gallop. You might also notice the calm surroundings interrupted occasionally by crow calls, trees rustling in the wind, or the occasional farm dog barking at the stranger barreling down the rough dirt road. Just someone in a hurry.

"I have been at work for some time building an apparatus to see if it is possible for personalities which have left this earth to communicate with us."

Thomas Edison, 1920

What if you nonchalantly recorded something around your house, let's say a music practice session. Then when you played it back, you clearly hear someone whispering. You didn't hear it when you recorded it, so what was it? Many unfamiliar sounds throughout history can be attributed to nature, machinery, and even hoaxes. As our post-industrial society grows, so does the list of unexplained sounds, like trumpet sounds from the sky, humming cities, and ocean whistles. The proliferation of audio and video technology has generated its own tally of the strange. Specifically, weird voices that have been inadvertently and unknowingly captured. These recordings and transmissions sound eerie but have a very unsexy-sounding name: "Electronic Voice Phenomenon," or EVP.

"I will never be an old man. To me, old age is always 15 years older than I am."

Francis Bacon

Dynamix turns fifteen years old this month. Well technically sixteen, because I incorporated a year earlier and did small jobs out of my basement until I could step out on my own. When I did, I couldn't have timed it better.

Read More...

"Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."

Arthur C. Clarke

To the average person, audio can be a mysterious "myth-terious" thing. Many people don't want to admit that they are intimidated by the technical side of it, and that makes sense. The closest most people get to manipulating audio is adjusting the volume on their stereo. I bust 10 common myths about recording audio.

Shadow: No, Mary. I suspected a trap, so after I opened the door, I walked across the room and stood behind them.

Apple Mary: But your voice.... it came from near the door.

Shadow: Ventriloquism. A simple trick of projecting the voice.

The Shadow

"The Blind Beggar Dies"

Radio broadcast: April 17, 1938

We're fooled by Mother Nature all the time. She uses light to conjure up a mirage on a hot desert day and Aurora Borealis on a cold Alaskan night. She also has a bag of tricks for sound, like flinging noises a hundred miles away. But one of her best is when she makes sound disappear. This slight-of-hand by Mother Nature may have even changed the outcome of several battles in the American Civil War. What are these shenanigans of sound? Magic? Illusions? Sorcery? As the old radio serial hero said, "Only The Shadow knows." They're called acoustic shadows.